Corte Mincio

Corte Mincio

Corte Mincio

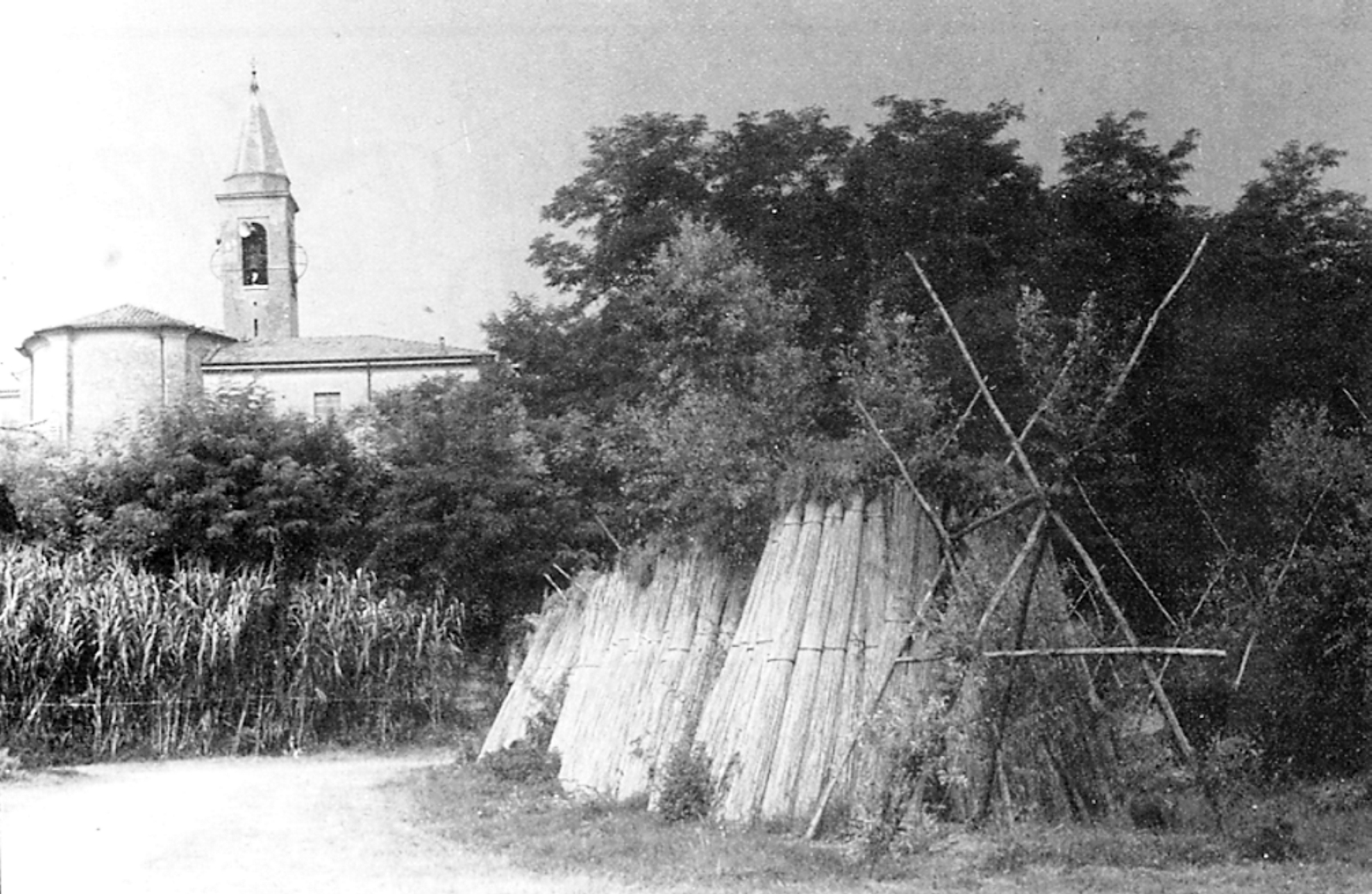

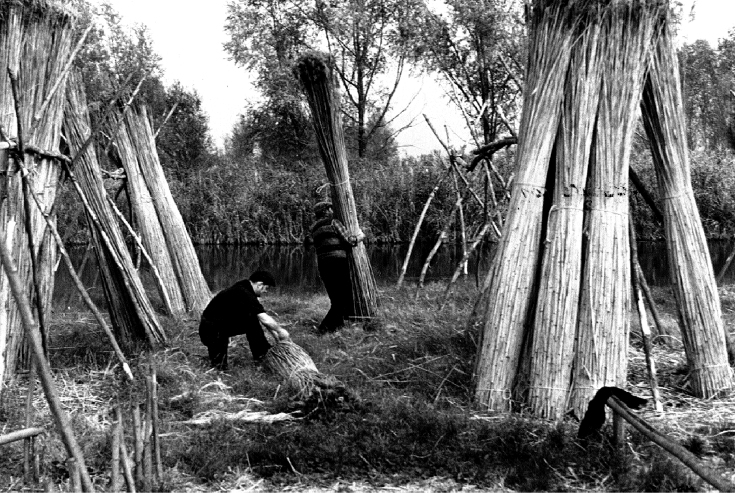

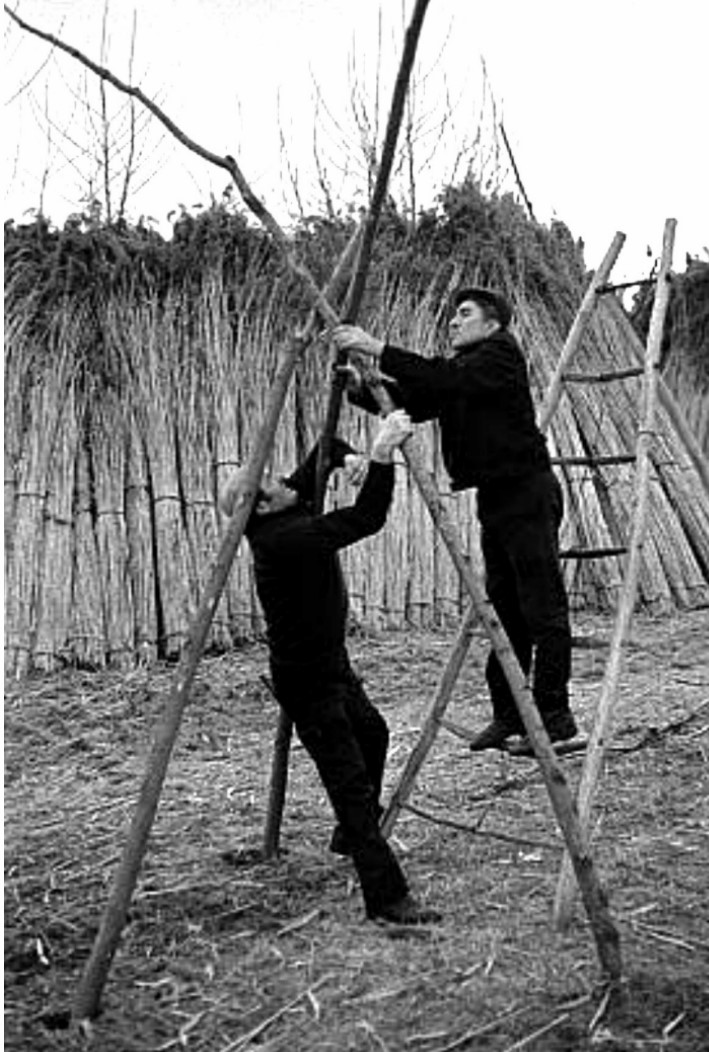

Corte Mincio was above all a workplace: warehouse and laboratory. A large space in which to store and subject the reed (in the local language, i canèi) and sedge (in the local language, careşa) to the first processes. It is the place that more than any other testifies how the Rivaltesi learned to govern the swamp, which in Rivalta sul Minicio is called the “Valley” (la Val). The Valley was “cultivated”, and its fruits were harvested. The swamping of the fields, for all an apparent disaster, was transformed into wealth. The Rivaltesi learned to know the Valley so thoroughly that they transformed it from an unhealthy place, into a basin that can be traveled with special wooden rowing boats (rem e puntal), marking and opening canals (li fösi) and keeping them clean. This was important so that the fishing nets did not get entangled and were always passable to reach the workplaces. They learned to aerate the shallow water by opening it to the wind and creating currents. They learned to make the marsh vegetation grow luxuriantly by periodically flooding the territory and making it healthy, using the fire at the end of the harvest wisely: the debbio, a stable and controlled burn. Activities that allowed the Rivaltesi to live in dignity. If agriculture could only be practiced in the summer, the Mincio, on the other hand, always gave its fruits: in winter the reed, in spring the fish, in summer the sedge, in autumn “al trigul”, wood and more fish. The work was distributed evenly between men and women, occupying a large part of the active population. Towards the end of the 1950s the business essentially revolved around four companies: that of the Benasi Fiore family, founded by Francesco Benasi in 1860; that of the Todeschi family, founded by Rodolfo Todeschi in 1894 and those of the Scalogna and Grassi family who, after a few years of collaboration, they continued their own business starting from 1938. These families together with the Belenghi, Tomaselli, Bernardi, Mozzanega, Bresciani, Lonardi and Tognoli gave life to a thriving business, so important that it even employed various workers from the neighboring villages. In that period a quantity of crude product equal to 15/16 thousand quintals of marsh cane and about 5 thousand quintals of precious sedge were processed. Rivalta sul Mincio came to be considered the Italian capital of reed and sedge. Then, from the beginning of the nineties, with the advent of new materials and modern technologies, these activities gradually disappeared. Therefore, it is necessary to keep their memory, because they represent important, unique and positive traditions. These are activities that have preserved the ecosystem of the Valley for almost eight hundred years. Although subjecting it to intensive exploitation, the workers of the Valley have left it unchanged, avoiding the natural burial only and exclusively for constant and interested care. Perhaps, an example to learn from.

Gent da Val

The Rivaltesi according to “Tom”

Gent da Val

Par ani e ani, istà e invèran, sgàlmari, mesurèl e fiaschin dal vin, la matina bunura șo in dla val, cun la batèla.

I part ch l’è scür e fred, che pena pena ’s agh ved: l’è gent gaiarda; i è lauradur vià a fadighi, calur, tavan, sansali e südur, a fümana, brina, nef…

Töt al dé a tach a chi pinòt: taià, cargà, dasténdar infin a nòt.

Töt al dé a tach a chi masun par arèli, arlin e burlun!

Insal Mens dla matina ala sera: laurà e laurà….a par gnan vera!

I sa mésia, i s’ dà da fa, sensa cincèl, sensa tant parlà!

Sulament dòp na smana ‘d fadighi e d’acident, at i vedi a fa “sàbat”

toti cuntent.

An piculin, insiem a l’ustaria e a mèsdé sa sdèlfa la cumpagnia.

E i arlunsi…cu li man pieni ’d seduli e s-ciapin, töt al dé li sa mésia

indi magașin cun arlin, arèli, störi, burlun e filferin.

Li filanderi ch li pasa i dé in mèșa l’udur da falòpa, indla fûmana dal vapur, cun li man sénpar in mòia indl’àqua bruenta par laurà la seda

dli galeti in màșara.

Tota gent sensa tanti “oimè”, seria, sensa preteși.

TOM ANNO 1993

Gente di Palude

The poem represents a portrait of the citizens of Rivalta, always ready to work, from dawn to dusk, with a thousand things to do to keep the town and its economy alive. The only time of celebration is on Saturdays, when the salary arrives, or when you meet in the tavern for a glass of wine before returning to work. Nobody ever complains. This is the life of the “people of the Valley”.

Testimonianza di Bruno Benasi

Testimony of Bruno Benasi, born in Rivalta sul mincio on 25 march 1943. October 2022

We meet Bruno to ask him to tell us about his work experience in the Valley. Bruno is a descendant of one of the four families who have made the history of the processing of marsh herbs in Rivalta sul Mincio, the Benasi. As a shy and reserved person, he approaches our request with a little hesitation but then lets himself go to the memories and it is a great pleasure to listen to him.

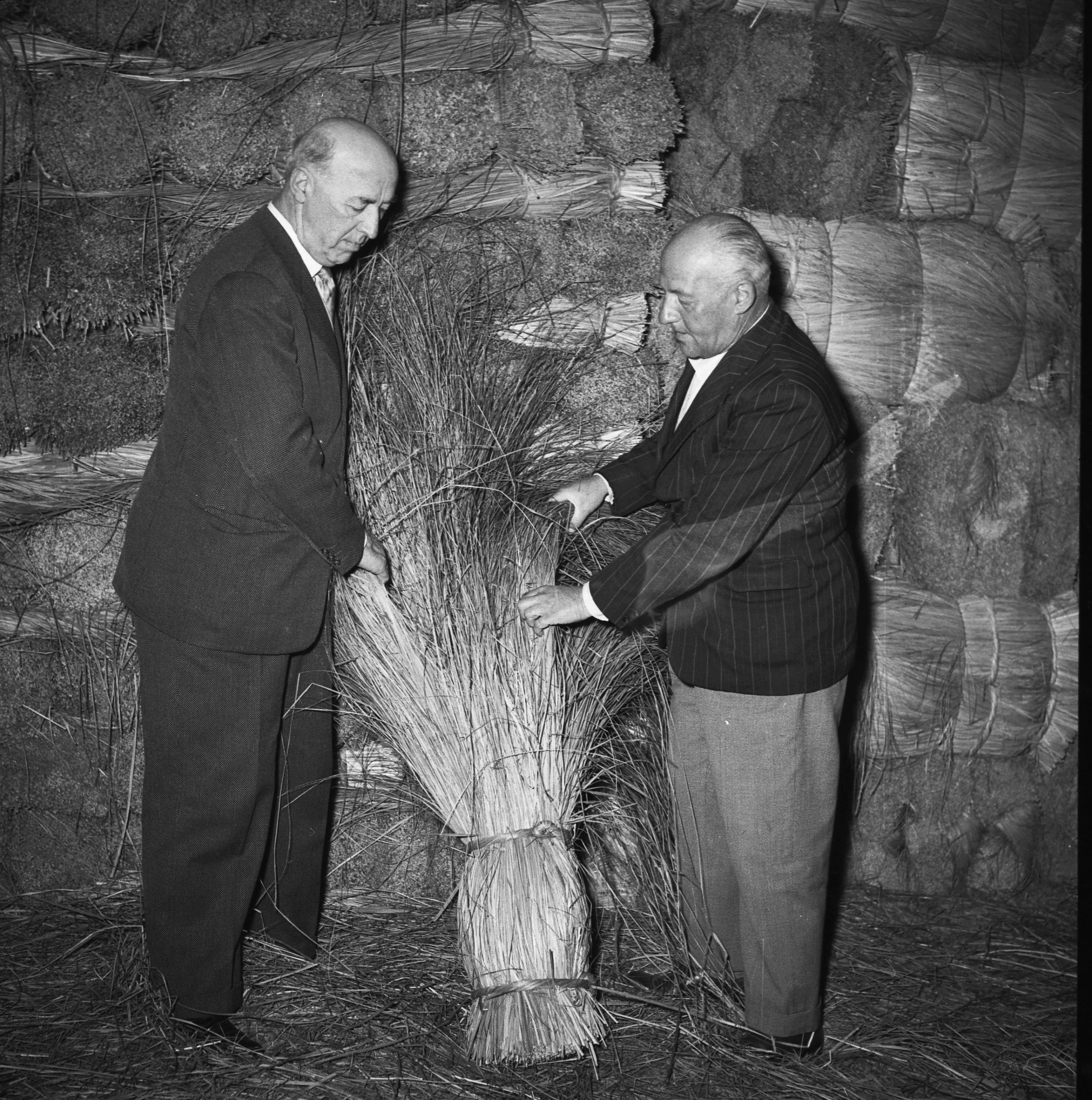

“… my grandfather Fiore started his business in 1860 as an agricultural entrepreneur. By taking care, at the same time, of the cultivation of the land and of the Valley, he was able to guarantee work for his employees for the whole period of the year, without having to resort to layoffs or what we now call “cassa integrazione”. The 120 land biolches located near the town of Rivalta were used for the cultivation of traditional crops. In the Valley, however, cane was collected for the manufacture of the “arelle” which, intertwined with the “pavera” (cattail), were initially used for the breeding of silkworms in the home and subsequently for the conservation of fruit, especially grapes. In the upper area of Mantua, the “arelle” were used for drying grapes used to produce sweet wines and in the area of Verona, on the other hand, to produce Amarone. Around 1915, after the death of my grandfather Fiore, my uncle Italo and my father Plinio took over the business, founding the F.lli Benasi fu Fiore farm. The first continued to take care of the cultivation of the land, while my father of the cultivation of the Valley, including the collection and processing of its products. The activity related to the processing of marsh reed expands rapidly also because the cultivation techniques of the Valley are learned with so much humility. The forced flooding of the reeds and the burning (the burn) of what remained on the ground after the reed harvest (leaves and remains of the marsh grasses that cannot be removed) ensured the growth of a healthy and fertile swamp. They also contributed to avoiding phytoremediation and represented an effective purification system for the waters of the Mincio, thanks to the filtering properties of the very long roots of the marsh reed. The sedges, on the other hand, were cultivated by creating special plots among the reeds. In nature, the reed is predominant on the sedge, because reaching considerable heights, it removes the light necessary for its growth. In addition, the sedge needs to grow in water to develop, just like rice. Therefore, to make room for the sedge, the cane had to be prevented from growing by cutting it definitively at the base. The collection systems were also different. After being cut, the cane was collected in large bundles, loaded onto boats and brought ashore where it was stored on special palisades (Frisian horses) awaiting subsequent processing. The sedge, on the other hand, after harvesting was spread out in the fields to dry where it remained overnight to let it take the dew on both sides and make it whiten. Then it was collected in bundles of 5/6 kg and left to mature in warehouses. Subsequently, with the “combing” the less strong and healthy caresa is eliminated and packaged in 5 kg bundles ready for sale. To be able to work it, it was enough to wet it with water and it seemed to manipulate the silk. In 1920 we started exporting our products to various European countries. In the following years the barrel was used in construction for false ceilings or for the manufacture of panels used to insulate walls or ceilings. With the “Targes” of the Grassi family, an agreed project is to supply the panels for the construction of those used for the construction of buildings in airports, and palaces both in Italy and in Europe. The “Targes” took care of their construction and installation, then they divided the profits “on word”, with fairness and respect for mutual agreements, which is unthinkable nowadays. With the cane, moreover, the arelle were manufactured for covering the flowers in the horticultural companies of Liguria and Tuscany, for the drying of bricks, for various coverings those of the structures used to protect the sites included, for the ceilings of the sheds of the poultry and pig farms and for window shutters. Arelle made with galvanized wire could last even 18 or 20 years. Large quantities of raw material were exported to Germany for use in construction. I remember that, through the railway, we also exported 120/130 wagons of product per year to that country. Since there was no lack of inventiveness, we transported the goods to the Castellucchio station using the American “Morris” jeeps which, appropriately modified, were able to tow large trailers. Agricultural tractors at the time could not travel on the road. Caresa, on the other hand, was exported to France, Belgium and Switzerland for the strawing of the chairs. In Italy, in some cases, it has also been used as a cover for bars and restaurants. The cane harvest began on November 1st and ended on March 25th. From 26th March to 15th June, it was cleaned and selected and from 16th June to 15th August, however, the caresa was collected. The winter working hours were expected to start at 8 until 13 and from 14 to 18. In the summer, however, work began at 7 until 11 and from 15 to 19. The morning ended at 11 because it was the custom that the employer work and workers had a nice refreshing bath in the Mincio before returning home for lunch and an afternoon nap. Fondomincio was not only a workplace but also an important place for socializing. It was possible to find Cleante Grazioli, son of Olga and Tarabin, who with his kiosk sold ice creams that are nowhere to be found. Just think that Cleante together with the other ice cream maker from Rivalta “al Ligio” had invented “il missino”: an ice cream very similar to the more recent “Mottarello”. They put a “ball” of ice cream flavoured with cream on a cone, dipped it in dark chocolate and the result was something wonderful. We worked until Saturday, then returned home not before having received the weekly pay. I remember that the arellaie were paid by the piece by agreeing on a minimum weekly production. Therefore, they could manage the work as they wished also based on personal ability. At the end of the 1960s, we had 105 male and female employees. I remember two moments of great difficulty. The first was the exceptional snowfall of 1954 where we totally lost the harvest; not a single cane remained standing. We lived the other in November 1951, the year of the great flood of the Po which also involved the Mincio. No problem for the Valley in this case, but a lot of inconvenience for people. In Rivalta the water reached the middle of the current via Porto and Mantua was completely flooded. I remember that the Carabinieri came to ask us for boats to take the Mantovani from the flooded city center to the peripheral areas to save them. In those years, hunting and fishing also represented an important economic resource. Hunting games were sold at auction at significant prices for that period or were rented to hunters who came from much of northern Italy. These, the evening before, were welcomed by the boatmen from Rivalta with a hearty dinner in the famous taverns of the town and after staying in the inns, they were accompanied to the Valley, the next morning, for hunting trips. At the beginning of the 1980s, the first signs of difficulty began to appear. It becomes increasingly difficult to find labor that is attracted to less strenuous activities, consumption changes and one begins to suffer competition from Asian products. I remember that I went out of business in 2000, the year in which I sent the last railway carriage to France loaded with marsh grass.

Video storico a disposizione del Circolo Fotografico di Rivalta sul Mincio, gentilmente concesso dalla famiglia Mozzanega

Opuscolo pubblicitario 3° Mostra Mercato della caccia della pesca e degli articoli sportivi

Pubblicazione dell’Associazione Pro Loco “Amici di Rivalta” in occasione della Mostra Mercato del 26 27 28 e 29 settembre 1969 a Rivalta sul Mincio.